The Coding Agent Data Deal

On user data control, coding agents as retrievers, and the value of your coding transcripts

This is a follow-up to my previous post about coding agents, focused on data implications. I’ll map the current options for user data control and then argue that much of agents’ newfound power comes from — you guessed it, data — specifically, (1) the coding agent paradigm makes it easy to retrieve data from user files and from users themselves as needed and (2) coding agent workflows generate high-value feedback data, such that users end up performing extra valuable “data labor”.

While this post is again pretty speculative (naturally — there’s a lot we don’t know yet about all the implementation details for building and deploying coding agents, though there are open efforts like Open Hands and many of the benchmarks in this space are open), we can start to think about some practical takeaways for labs, users, and the role that public AI bodies can play in helping people use coding agents safely and effectively.

Section 1: The Coding Agent Data Policy Gap

And why you should probably opt out of “help improve AI systems” right now, even if you love AI and/or AI companies.

Something that is massively under-discussed in the midst of the AI coding hype is that coding agents appear to be effectively operating under a separate, less user-friendly data regime than the corresponding web applications. It is not yet clear how privacy policy claims about allowing users to delete data apply to coding agents. More generally, it just isn’t clear what aspects of AI lab privacy policies apply directly to coding agents.

Of greatest concern to individual consumers using coding agents via subscriptions, it appears that no major coding agent actually offers consumers (i.e. non-enterprise users) any functionality to delete individual coding agent transcripts from lab servers. As far as I can tell, if you include something secret in a coding agent chat, your only recourse right now is to delete your account or toggle your “help improve AI systems” setting off and wait for the data retention period (30-day for Anthropic and OpenAI; more complicated for Google products) to expire (please do tell me if you’ve seen anything to the contrary and I will update!)

A “transcript” here is the full agent interaction log produced when you use a coding agent (which might include not just your prompts, but also records of actions the agent took, like reading your files or running tests on your computer).

As a concrete example, let’s say I open Claude Code in my “Documents” directory. I ask it to help me make a custom note-taking app. Claude takes a look at my notes currently sitting in my Documents folder, but I made a mistake — I forgot that one of those notes contains a sensitive medical record! Of course, I don’t think Anthropic is going to do anything nefarious with those records, but if I could, I’d probably want to go online and click “delete” on that transcript.

Even if you’re very excited up about these AI tools and want them to succeed, your best option would be to turn the “help improve AI systems” setting off so that eventually, the transcript will be deleted.

There’s major tension here, because I do think that people will benefit a lot from trying out these coding agents (both for their own utility and enjoyment, but also to get a real sense of the current level of capabilities to react appropriately).

The Situation Right Now

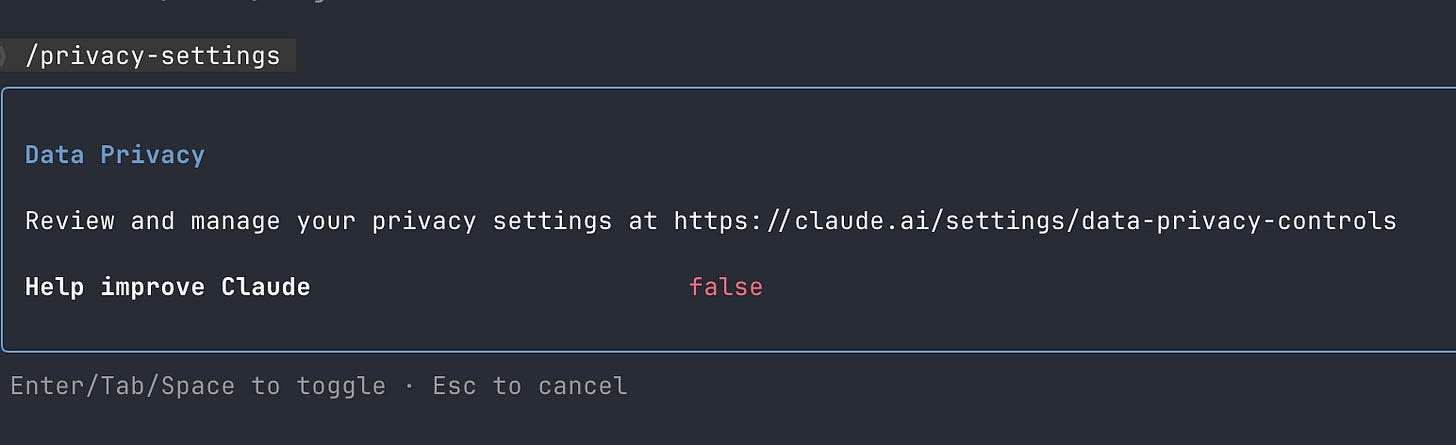

As of January 2026, Claude Code gives you just a binary choice to opt out (no training, 30-day retention) or opt in (data used for any kind of R&D purposes, 5-year retention). The Claude Code tool (shown above) directs you to the main Data Privacy Controls page and the Privacy Policy. The Privacy Policy discusses the standard web app features for deleting chats, and it seems that Claude Code uses the same Privacy Policy as the Claude chatbot.

However, there’s a separate Claude Code Data Usage docs page, which explains your two choices: “Users who allow data use for model improvement: 5-year retention period to support model development and safety improvements” and “Users who don’t allow data use for model improvement: 30-day retention period”.

Critically, if you go looking, you will find there is no web page where you can view what transcripts are being stored on the Claude Code servers and what data is in a given transcript (and the same seems to be currently true for Codex and Gemini).

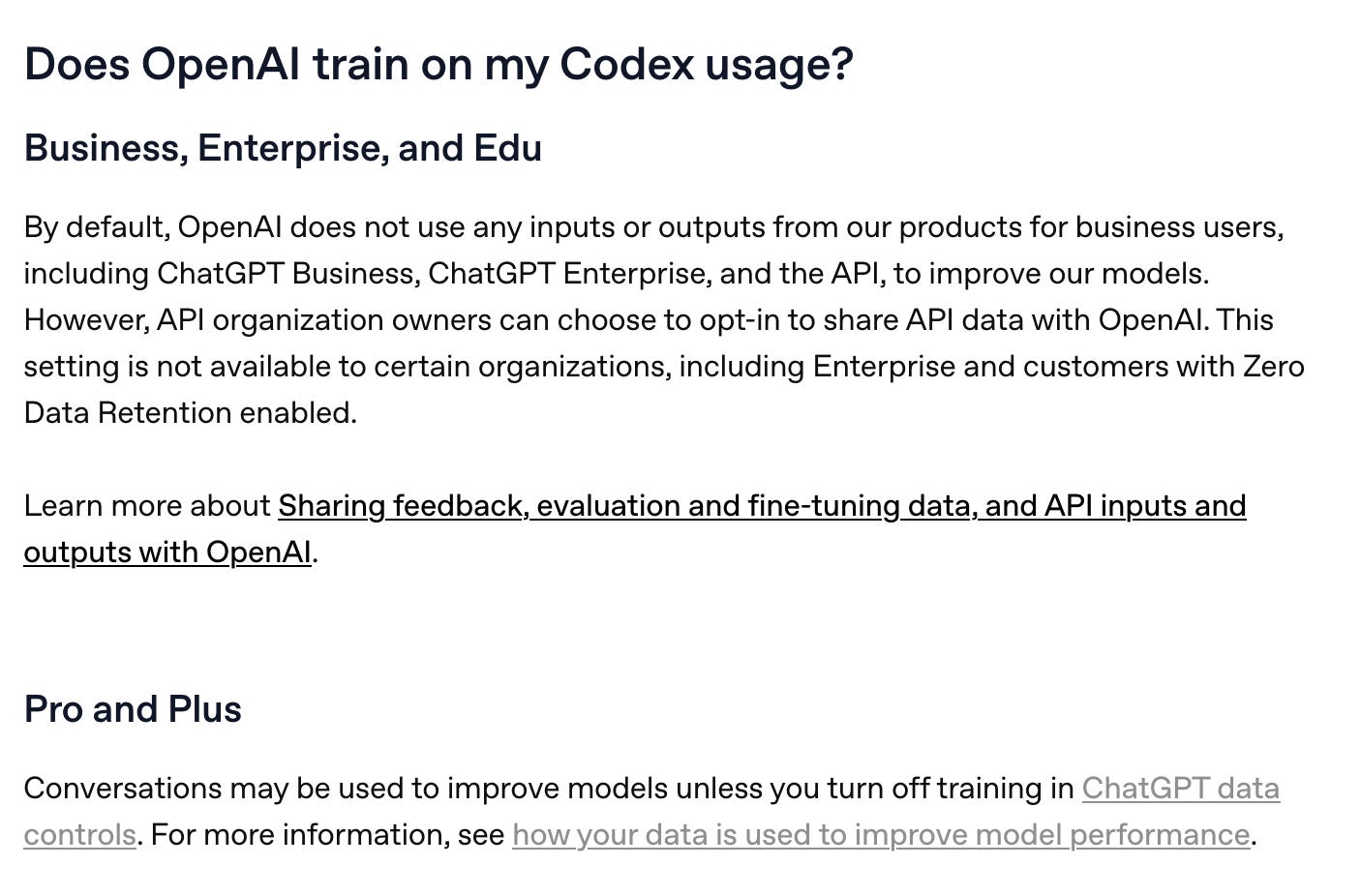

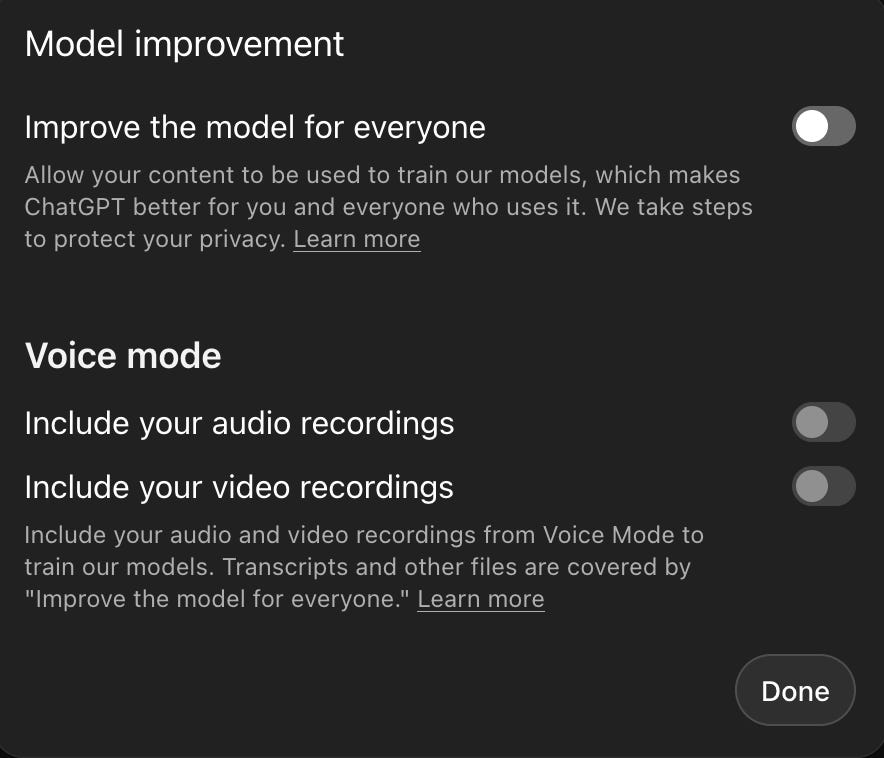

If you’re using OpenAI’s Codex via subscription plans (documented here, which links to the in-app data controls and this article), you also get a binary option to help train or not.

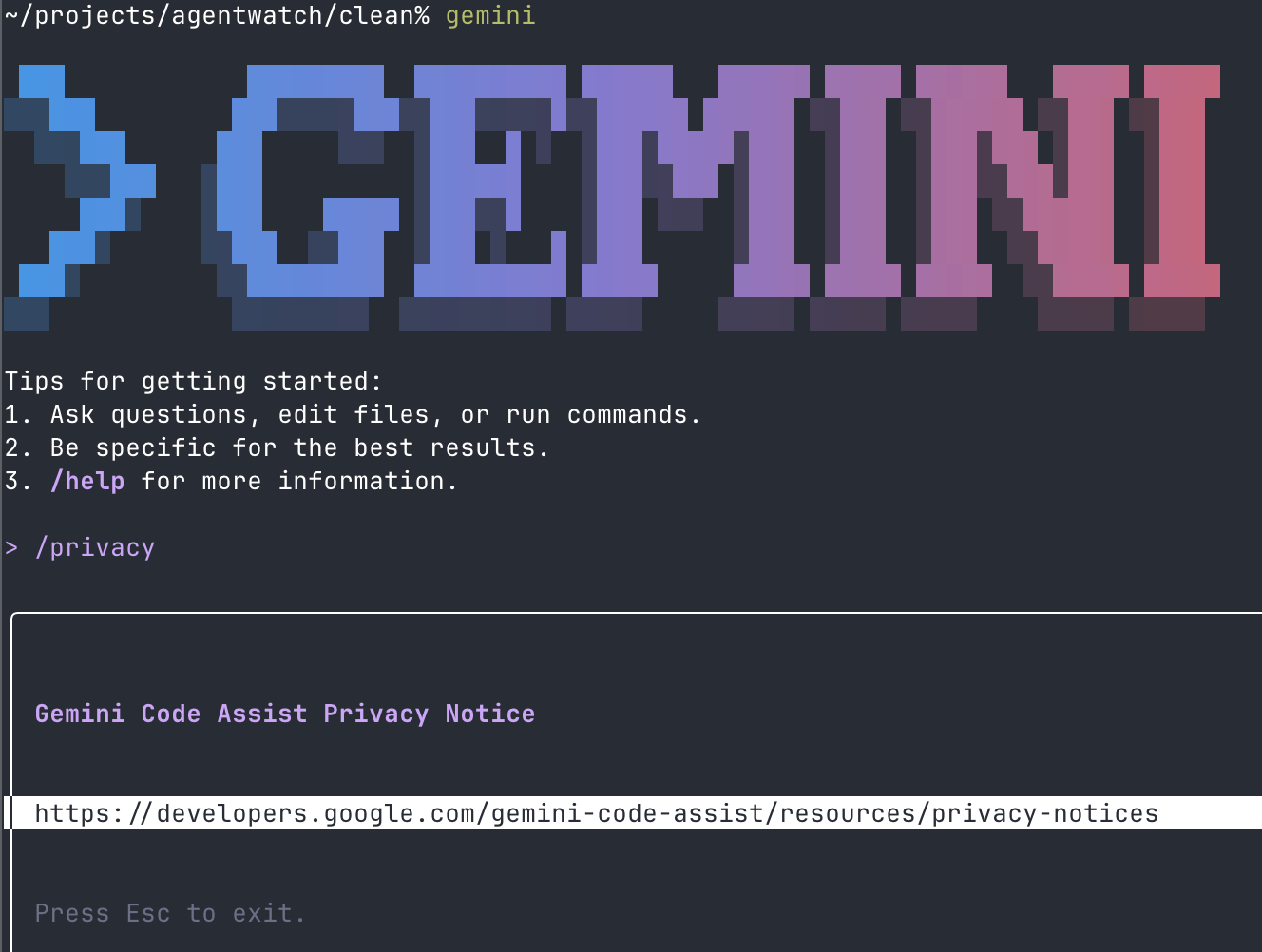

Gemini CLI does have a privacy command, which takes you to a rather complex “Gemini Code Assist: Terms of Service and Privacy Policies” page. There’s also this documentation page that is CLI-specific; there is no mention of deletion in the CLI docs. Depending on your account type, you may be exempt from training, but here I could not find any kind of interface for viewing or deleting individual chats. Further, usage by free-tier users is anonymized such that deletion is impossible. The advice for individuals is: “Please don't submit confidential information or any data you wouldn't want a reviewer to see or Google to use to improve our products, services, and machine-learning technologies.”

What this implies

I think the discrepancies and complexities here are most likely due to the breakneck pace of development in this space (Claude Code, Codex, and Gemini CLI software are getting constant releases, etc.) and not due to anything nefarious. Given that coding agent data is really high value compared to other forms of AI usage data, it’s possible that some parts of the current approach are at least somewhat intentional. For instance, it might be part of an explicit subscription business strategy to offer subsidized API access in exchange for data. Interestingly, that would let us do some external value estimation using the price point difference. It’s notable that these practices seem pretty consistent across all of Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google.

My recommendation

This means that if you’re recommending others to try out coding agents (as I implicitly did in my previous post1) you should, until this changes, almost always recommend that all users select the “opt out” option for all their AI services. If you’re concerned about data use, you also should not use Gemini unless you are a paid user.

More strongly: even if you are the world’s greatest fan of Anthropic/OpenAI, or just a huge fan of AI in general, unless you’re absolutely 100% confident that (1) your files are perfectly organized, (2) you have excellent discipline with respect to managing agent permissions, and (3) you are going to use containers or virtual private servers every single time you use a coding agent, it probably makes sense to select the maximally “opting out” options across the board. If you’re worried about helping to train your own replacement, of course, you have other reasons to opt out.

While this might read as pretty critical, I am currently still in the “massively excited and having so much fun” stage of interacting with coding agents. I am also feeling a fresh surge of hope about how they can support a really healthy data and content ecosystem. I want them to succeed!

And an additional note: I expect these companies to act in good faith regarding data protection. I think the existing work from OpenAI and Anthropic that studies AI usage using privacy-protecting techniques has been very helpful and posed minimal risk to users. But it is important for users to know that that if they do send some kind of secret information to one of these tools, you have some recourse other than deleting your account or waiting for data to expire (though presumably if you switch to opt out, that data will just sit untouched for 30 days). And perhaps even greater threat to the median user, as I’ll discuss below, is simply that you help train your replacement without receiving compensation (beyond subsidized API access), and so you might want to delete data purely on this basis. Or you might want to delete data because you’re worried about contributing to a particularly concerning AI capability.

Section 2: The Agent Workflow Gets Users to Help Out with the Retrieval Problem

Now, onto a discussion of two data-centric reasons that I think these agents are so good. First, I think the agent paradigm elegantly solves a hard problem for AI companies: getting access to the correct set of retrieval data to use at inference time.

Traditional chatbots require careful retrieval system design. Builders must choose which domains they will attempt to retrieve from, and how (for instance, a pre-built index, some kind of search tool, etc.). The first versions of LLMs had no search at all; they just do inference using their weights. They are “purely parametric” (relying only on what's baked into the model's weights, with no external lookup). Then people started adding web search tool calling, more sophisticated “Retrieval-Augmented Generation” (RAG) systems, and so on. This required picking the correct search API, having subsystems for selecting candidate items to be retrieved and then ranking them (see e.g. older work on passage retrieval for one conceptual frame). It also required (and still requires) negotiating access deals with content providers.

When you run coding agents on your machine (for instance, running the Claude Code CLI tool or Claude Code Desktop) or hook up a cloud-based coding agent to your coding repository (for instance, using Claude Code from the web), you’re providing a ton of data to the agent that can be retrieved at very, very low cost. It does cost some tokens for the agent to search and retrieve your files, but this is low cost relative to alternatives. This data is also very likely relevant to your task! In other words, the agent paradigm gets users to voluntarily provide their own high-quality context-providing data: codebases, files, notes, documents.2

For now, these tools remain somewhat “human-in-the-loop”, so agents can also prompt the user directly to get the information for them. For instance, if a web link is blocking AI traffic or the agent needs the user to run a terminal command, they can somewhat cheaply ask the user to intervene (it does cost your attention).

I think this fact partly explains why agents feel so much more capable than web-based tools. You can be sloppy in your prompting; the important structure is already in your code, docs, tests, and so agents can “correct” your sloppy prompts by retrieving key information from your actual data. And if you really get into agentic coding, you’ll eventually probably start to reorganize your filesystem and your digital organization more generally to help the agents work. You are essentially building and curating your own retrieval system for the model.

Also, something very important to consider in connection with our discussion above about user data policy: under the current terms and policies, if you use agents in “opt in” mode, you are potentially contributing your entire repository and maybe even your entire filesystem to a lab’s training set!

Section 3: The Testing Loop as Implicit Data Labor

Another reason why agents are likely so powerful, that is very much a case of a ‘data flywheel’, is that in the course of regular agent use the user ends up producing records that serve as feedback for improving AI. One way I might frame this argument is: because agents are now very good at tool use and thereby lower the friction for a lot of tasks, they also drastically lower the friction for users to communicate what success means in their specific context. There’s a sort of compounding here: agents make it easier to write tests (perhaps in the pre-agent era people would barely even have time to write tests for their hobby side projects) and then the presence of those tests makes the resulting data more valuable. (Of course there will be cases where an agent outputs bad tests, the user never looks at the tests, and the resulting transcript is not very high value. But there will also be many cases where the user does provide real signal about success and quality).

We can also note here that many LLM coding “hacks” being shared around right now involve getting the agent to help you produce structured data that measures success beyond just unit tests; e.g. having the model interview you, having the model use browser automation to screenshot a web app you’re working on, having the model simulate various user personas, etc.

When building a standard “original-ChatGPT-style-chatbot”, AI companies faced the same problem search engine builders have long faced — it’s hard to know if the user walked away happy. You can use proxies, like “dwell time”, click data, and other related measures3, but you can never be totally sure what happened if a user makes a search query, the results were poor, and the user walks away from their computer. There’s no mandatory thumbs up / thumbs down or satisfaction score, and very few users do that kind of labeling naturally. This was also true of purely parametric language models.

This is not true for the standard use of agents!4

Instead, for coding projects, the workflow probably looks like this:

a user writes some prompts, perhaps providing a detailed specification for some outcomes

agent writes code

agent runs tests (they might prompt the user to say, hey want to run tests, want me to write tests)

(sometimes) user reviews/updates tests

(most of the time) user actually uses the software/outputs, and then sends new prompts saying “thing X didn’t work” or “thing Y worked but it’s too slow”.

If the system outputs logs to a file, the coding agent can read those logs! The coding agent can see the number of successful tests, and so on.

This creates dramatically richer signals than clicking thumbs up/down for a chat model. It also guarantees that if you continue to code, the transcript contains signal about success and failure. Transcripts will even likely contain details about the success/failure rates of subagents deployed by the main agent, or specific tool calls.

When a coding session is over, the transcripts (which labs have access to) now contain a full “trajectory”, the prompts, the files that led to the outcome, and the actual working (or not working) code itself!

Section 4: Two Different Privacy Problems

In Section 1, we looked at the current set of options for data control available to users (as of January 2026, quite limited). This is concerning from a privacy perspective, and indeed one of the first concerns many people might have is, “Is this agent going to read my Social Security Number and my bank password and my medical records somehow?” (The answer is, if you’re not very careful, it might. Maybe for some users this is intended behavior.)

I think these concerns are real, and I definitely expect there will be some clarity regarding the application of privacy policies and data control to this kind of data in coming weeks. However, there is also a secondary privacy concern: while providing the agent with your data at inference time gives you better results (good!) it is almost certain that giving this data back to labs will also make it easier to train future agents to replicate your behavioral patterns, decision-making styles, problem-solving approaches. These are things that cannot really be “anonymized” or “redacted”, and they are potentially very consequential.

For this reason, having some kind of data control via technical means will be very important. Perhaps in the long run as these tools diffuse into the workplace, more people will use them via enterprise API contracts and not personal subscriptions, and this will be partially solved (in many of these discussions, I do think that simply applying enterprise standards to individuals solves a lot of problems; it also suggests that perhaps a quick and dirty approach to data collectives in this space is simply making a consumer co-op to buy API credits for coding agents).

Section 5: The Collective Opportunity

Now to end on a hopeful note!

Reiterating my previous post, while the confusing data policy is a cause for concern, the fact that the default behavior of coding agents is to also give users easy-to-access full transcripts on their machine (you can very quickly have a coding agent give your own small browser app to browse your own transcripts!) opens the door for easy-to-join collective action. If we solve the redaction and filtering problem, we can easily pool transcript data. If we legitimately enrich that data, collectives could potentially sell this enriched data back to labs. Practically, this might require collective members to use the API as described above in order to have bargaining leverage, though it’s possible they create so much value via pooling or enrichment that AI labs would be willing to pay.

As has been the case for a while, any regulatory interventions or privacy advocacy that increases data control will shift bargaining power toward users.

In many ways, I think the coding agent paradigm actually opens the door to a very pro-privacy vision. Imagine this: some lab (or public body) operates a service that basically lets a user easily log in and run coding agents from an ephemeral virtual machine (this might just be a web app that’s basically a friendly and fancy interface for SSH-ing into a “virtual private server”). The user would upload specific files they want to work with (or even connects their whole filesystem) and the server would be wiped afterwards. If that service guarantees that (1) transcripts are only retained by the end user and (2) the private server is actually wiped after the session is done, this is actually an incredibly privacy-friendly approach to AI.

Another angle is to lean more heavily into supporting local inference, which would be even better from a privacy perspective. If locally running coding models can close the gap with frontier offerings, this could become a viable standard practice.

This is doable today, the main barrier is simply that subscription access to coding agents is such a good deal compared to API access. So it might just take some cost reduction to make this viable.

And to be clear, I do think people should try out coding agents or at least be exposed to their outputs to get a sense for the current capabilities. There’s really serious risk that a bunch of organizations base much of their AI strategy and AI-related policies on assumptions about the capabilities of previous models!

See e.g. works on clickthrough data, implicit measures for web search, dwell time, and satisfaction.

Note: you could set up your own special, bespoke adversarial set of usage procedures where you do things like ban the agent from running tests, obfuscate certain information, make heavy use of sandboxing and siloing. You could keep certain critical information in a different directory, and you could probably get pretty close to a usage flow where you have the agent doing some tasks and then you’re manually running your test secretly in the siloed area. Even in this extremely adversarial setting, though ultimately if you continue to use the agent in a repository and make progress, it will see your code progress, it will see what’s going on, and so there’s still going to be a proxy signal for success going back to the AI operator.

There is some signal when we look at web search logs, but it’s not very rich. The default is that coding agent logs are very rich. You can take some obfuscating, adversarial actions to make them a little less rich, but it still is really hard. If you’re using coding agents that aren’t running locally on your machine, you’re almost certainly going to be sharing these powerful signals with AI companies.