"Many Models" and "Track Changes" for AI: Some Thoughts on LLM Interfaces

Interacting with many models and harnessing the power of `diff`

In this short post, I want to discuss two ideas about how we might expand upon LLM interfaces. These ideas have a “data angle”, as well. I was especially inspired to write up these current thoughts by this wonderful recent post by Nicholas Carlini, which includes a slew of great examples of how people might use LLMs right now.

Another motivation for writing this post is that I think these ideas can be particularly helpful for students using LLMs in an educational context (a topic of great contention, even as we finish up year two of the ChatGPT era). I’m very keen to hear feedback (and perhaps some of the questions I’ll touch on here have already been studied).

Carlini’s post has a really nice section that “scopes” that post (and acknowledges the serious issues with LLMs). In that spirit: I think LLMs are useful right now (and are a shining example of the power of collective intelligence), there are many tasks for which they are not still not all that useful, and there are major societal concerns stemming from the paradigm underlying LLMs and the use of LLMs (of particular concern to me: power concentration, training data issues, and job displacement). I think improvements to LLM interfaces might make them even more useful and help address the societal concerns at the same time.

#1: Many Models Interaction

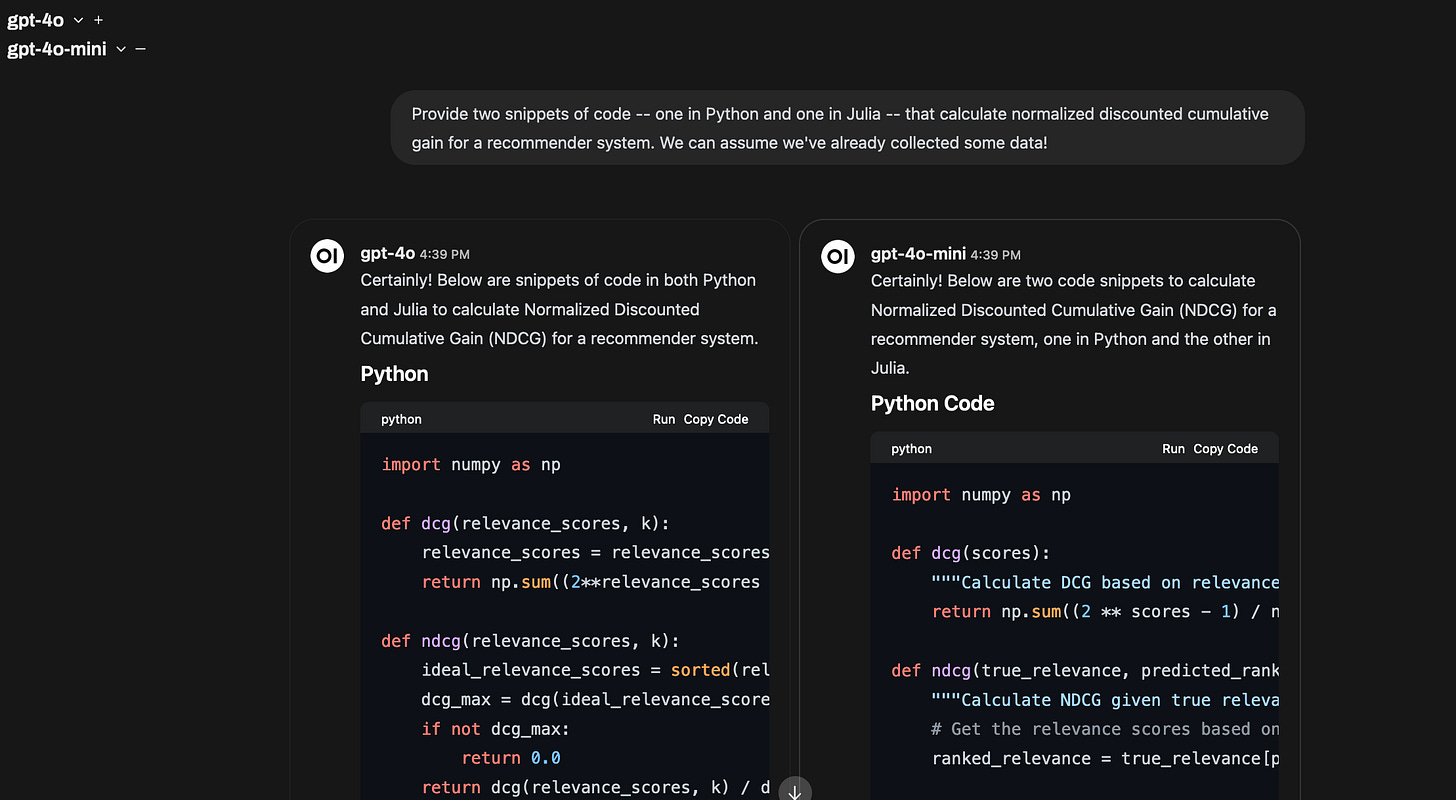

Using Open WebUI to chat with two models at once — simple, but potentially very effective!

First, I want to argue for something that is achievable right now, but not yet widely used (as far as I know): making a regular practice of interacting with multiple models at once. You can do this now with tools like Open WebUI (and people are using this in practice), though it requires a bit of set-up and access to an API key.

I believe the best way to interact with LLMs for many tasks will involve sending the same query to many models at once and viewing the results side-by-side (to start), and using more complex techniques to visualize the differences between responses. Perhaps these interfaces might highlight the “edit distance” between items, and drawing on my next point, looking to popular “diff” interfaces. Future interfaces could even go a step further and (1) allow users to “weave” together model interactions (efforts to make this easier are already underway) and (2) learn from user preferences over models.

An issue with this approach is that using multiple models increases one’s cost per query. It could seem rather wasteful if implemented poorly. Eventually, I do think it’s possible that query costs to made more legible to users (subscriptions with more rate limiting, or products that actually charge price-per-call aimed at non-developers). In this circumstance, users could make their own calls about if adding more models for a given call seems worth it. Even if users primarily use LLMs through subscriptions, there are still opportunities to mix together cheaper models in a way that actually gives cost savings in some circumstances.

The data angle: Interacting with many models at once provides the opportunity to produce very rich interaction data. Imagine a dataset describing a large pool of users who complete similar tasks (e.g., writing their dream TODO app) with four models at once. This dataset would be useful in revealing preferences over models. However, we could go a step further and even use this dataset to see how, and when, models might “boost” each other.

This approach could really help people reap some “collective intelligence” when it comes to choosing between models. There’s also a strong data portability argument here: if this were the default interaction modality, it would be a lot easier for users to manage their data across different models and organizations.

Of course, given the current state of play and political economy, it might be hard for private organizations offering paid AI products to support “many models” interfaces. Most obviously, Google probably doesn’t want to call the OpenAI API from its products (and vice versa). But this doesn’t mean that private companies don’t stand to benefit from many models interfaces. A single private organization that’s competing for user subscriptions and API calls could still let the user interact with multiple of that organization’s models all at once, with the same benefits.

An organization that gets this interface right (and there are certainly tough challenges to solve here, in particular around the communication and visualization of uncertainty) could get a serious boost to their data flywheel.

This idea also might run into some challenges around existing Terms of Service. If I’m constantly weaving model outputs together — say, having a conversation with ChatGPT and then sending that to Claude — I might be knowingly or unknowingly abetting the act of “training on model outputs”.

One vision for the future of LLM interfaces: the many models interface might be a piece of open-source software, and the actual hosting of the interface could be operated by a public body. I believe there’s actually a really strong argument to do this from a competition perspective.

#2: More Use of (Fancy) Unix-style Diff Interface

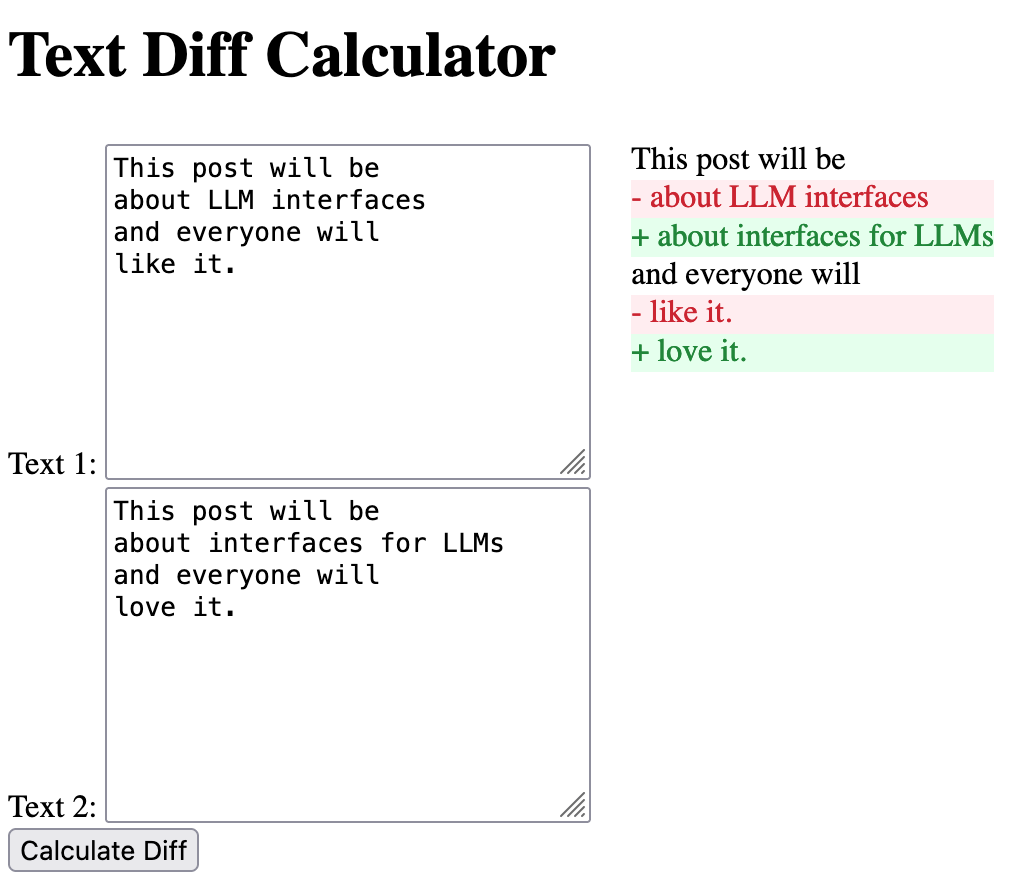

A very simple “diff calculator” (produced by GPT-4o).

Next, I think LLM interfaces should really lean on interfaces used to display unix-style diff outputs as a way to communicate how artifacts change over time, even for non-coding contexts. We should be reading diffs a lot more often.

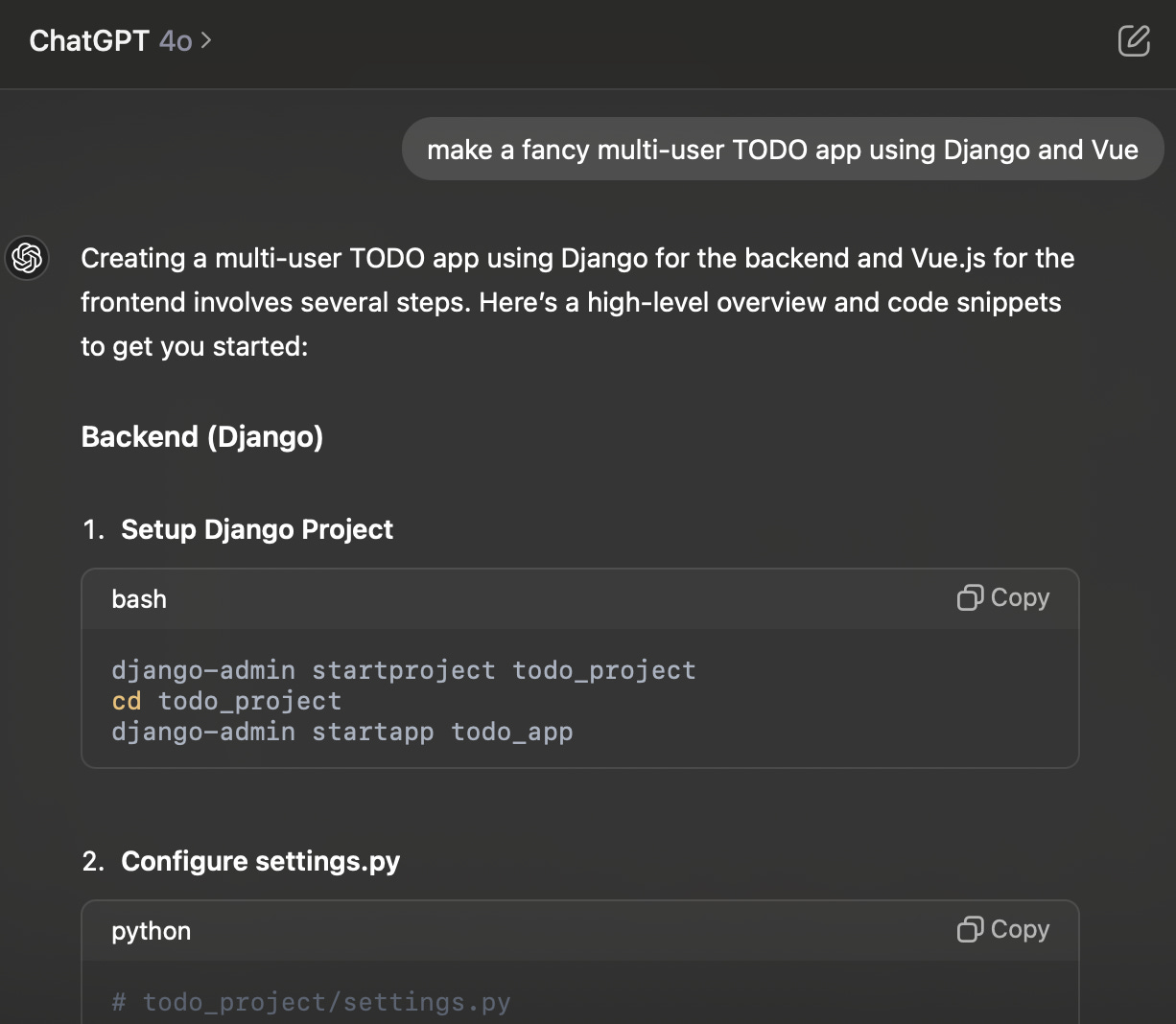

Imagine we want to use GPT 4o or Claude Sonnet 3.5 for something like, “make a fancy multi-user TODO app using Django and Vue”. The typical interaction could start by sending that query verbatim. The interfaces will give you some code (Claude can store “Artifacts” and ChatGPT will print directly into the chat). (See the Carlini post again for numerous examples of this kind of flow).

You might then run some scripts as instructed (or perhaps you’ve already done so), paste some code from the chatbot in your editor, run into some errors, paste the error messages into the LLM interfaces, ask for some new features, and so on and so forth.1

You could choose to make a commit for each every LLM-assisted modification. Some of you might already do that by default. My guess is that interfaces that push users to do this even more — even for non-coding tasks — can improve the user experience on a number of fronts. I’d go so far as to hypothesize that some version of this idea could improve both “final artifact quality” and educational outcomes. Of course, presenting “diffs” of non-code outputs is not trivial. These interfaces might look to more familiar “Track Changes” found in software like Microsft Word than to GitHub, but this will be an open design challenge.

Of course, taken to the extreme, an interface that over-prioritizes diffs could be unhelpful. In general, the right cadence of making commits and looking at diffs is an art and not a science, and commit norms and practices are team/organization specific for good reason.

I expect a nice, diff-heavy interface could be a great way to tell the story of how an LLM edited your code, and this will be particularly useful if ever using LLMs in an education context (if/when being a longer debate).

The Data Angle: Of course there’s a data angle here as well. I’m particularly interested in how the possibility that a diff-centric view (for non-code and code tasks) could substantially approve how people interact with their chat history and give fine-grained feedback. What I’m specifically imagining here is a big focus on feedback to LLM that looks a lot like a kind of code review and paper review, complete with references to specific lines and changes.

I’m hopeful we’ll see some evidence about these kinds of interfaces soon. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts, and especially if you know of anybody using these practices regularly (and especially if they’re collecting and/or sharing the kind of data described above).