Coding agents are (1) a big deal, (2) very relevant to data leverage, and (3) able to help build tools that support data leverage!

Sharing an early reaction to recent coding agent discourse and two relevant projects

In December 2025 there was a fresh wave of hype about LLM agents, especially the use of Anthropic’s Opus 4.5 model in conjunction with the “Claude Code” software. After spending a lot of time with these tools, I have to say I agree with much of the hype. It really feels to me like the “Claude Code moment” is a second “ChatGPT moment”. New agentic tools (specifically, LLMs that have the ability to search your files, editing them directly, search and interact with the web, and so on) make LLMs feel really useful, in a way that feels like a step change.

Using something like Claude Code is a bit daunting if you haven’t spent much time in the terminal (but Claude Code is pretty good at helping you learn as you go1). However, there are also options to use these tools from the web. These still require some configuration (Claude Code on the web integrates with GitHub repositories, so you need those), but I expect this kind of interaction will get easier and be integrated into general audience AI tools pretty quickly. It also means, somewhat weirdly, that even if you don’t care about code specifically, if you put your documents and data of interest in a GitHub repository, you unlock a lot of potential value from having Claude Code interact with those files instead of a just uploading those files to a web-based chatbot.

Beyond a potentially frustrating learning curve, there are a lot of legitimate security and privacy concerns with giving “agents” access to your files, your API keys, etc. There’s always the lurking fear that an agent does an accidental “rm -rf” over your whole machine (i.e., deletes all your stuff!).

The tools are so useful in part because you extend some of your agency to them — you give them GitHub API access, other API keys, etc., so it’s not just your computer at risk, it’s anything that can be touched by your API keys! There’s also a huge moral responsibility, in my view — if you have a “powerful” API key, you need to be very careful about which agents you give that API key. It’s not so different from hooking an agent up to a powerful motor.

Also, these tools are expensive!

In time, I think these problems will be solved, but the risk involved with coding agents and coding transcript data is quite high and will require users to adopt new practices (for now, we should probably be running most agents in containers or in virtual private servers, which creates more barrier to entry2). There’s also some OS-specific sandboxing options, but the interaction between sandboxing and various permissions settings is still pretty complex. I’d also like to see more documentation around how data access/deletion/retention choices from the web app interact with coding transcript data — this wasn’t clear to me. (I’m trying to address some of these issues with the Agentwatch project, described below).

The Data Angle

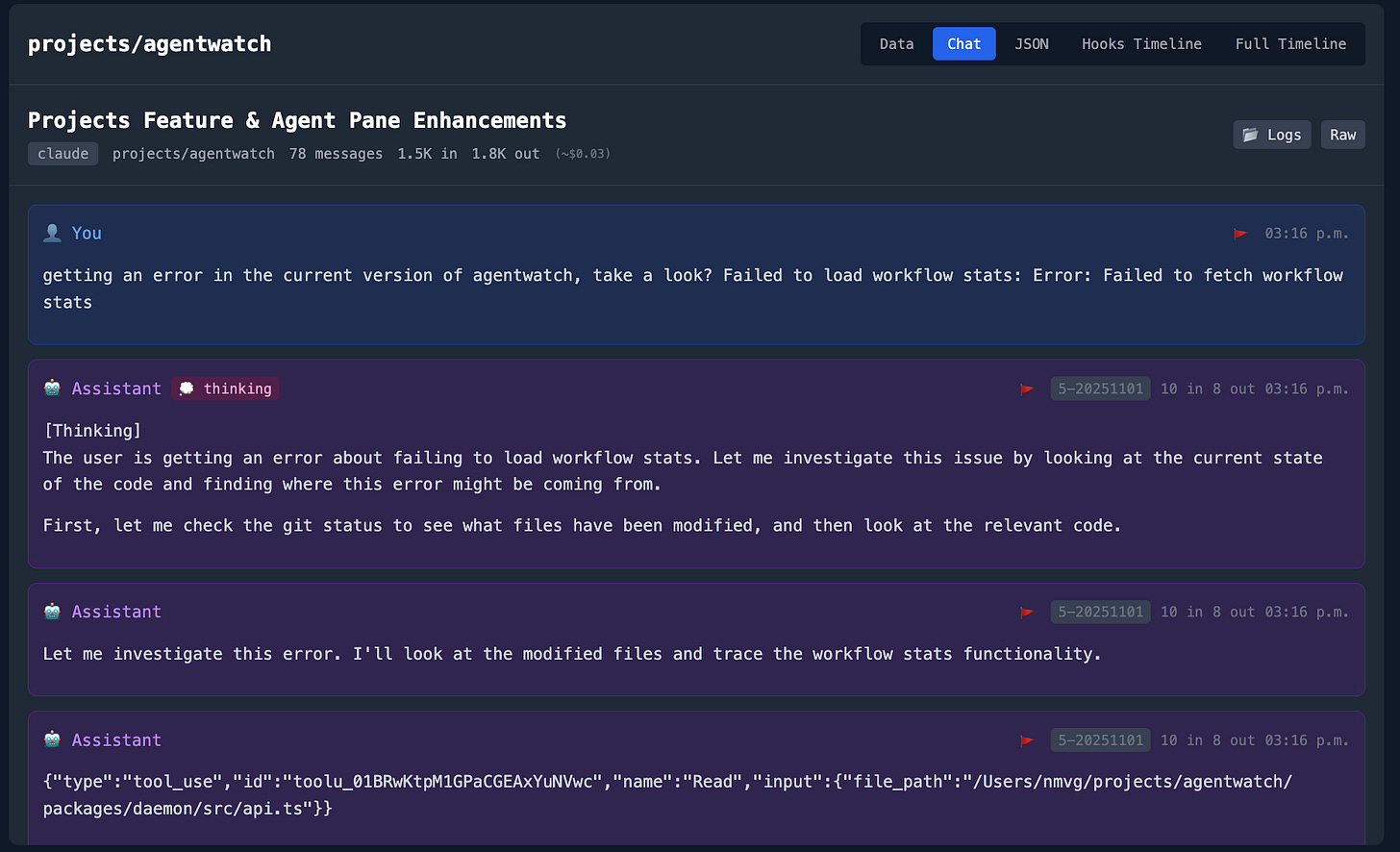

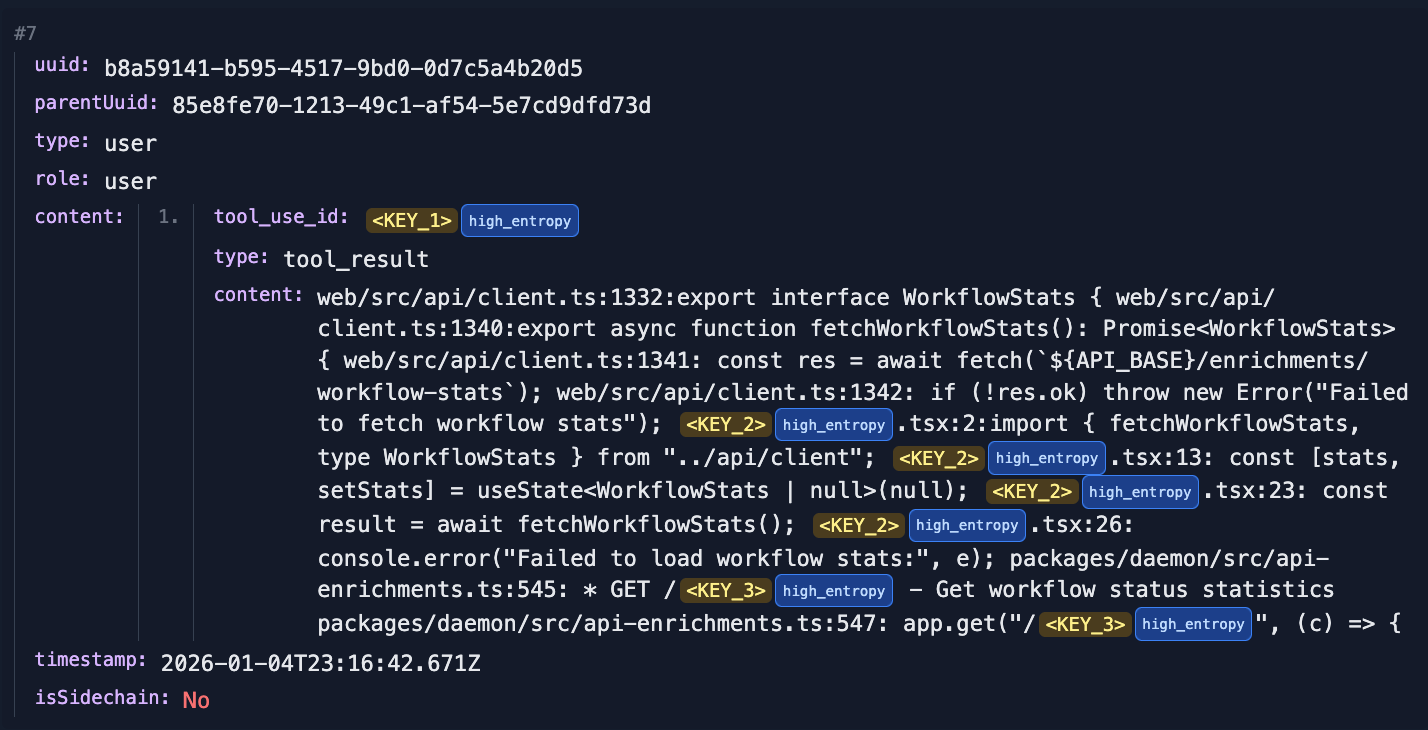

Coding agents create the potential for a fundamentally different kind of user contribution than the text-based training content (blogs, repos, etc.) and traditional data labor (annotations, etc.) that we’ve discussed in the past. In some ways, they make it really easy to merge content and signal. Claude Code (and similar agents — just going to keep using Claude as a running example) transcripts are quite rich. You get some actual reasoning from the model (Is it everything that’s happening behind the scenes? Probably not! Do reasoning choices provide true explanation of model behavior? Not necessarily!) Importantly, you can see all the “Tool Calls” — which include the instances where Claude Code is reading your files, taking actions, etc., and you can log, monitor, and interact with tool calls via the “Hooks” API — Agentwatch also takes advantage of this.

Also, a very simple but important aspect of the current implementation of coding agent tools (this may not always remain true, but I hope it does): the default behavior of these tools is to give the user structured rich data on their machine! No need to write a scraper to exfiltrate your chatbot-of-choice data. It’s there on your machine by default. (This won’t be true if we see a shift in emphasis on web-based agent tools; and again, there’s a good case for this from a privacy/security perspective. It’s complicated!)

An agent transcript includes your initial prompt, the agent’s reasoning, the tools it called, the errors it encountered, your corrections, and the eventual success or failure. In other words, if you contribute an agent trace, you’re contributing something closer to a somewhat labeled dataset of problem-solving than a corpus of finished prose. The value of these traces could exceed equivalent-length static text, because they encode process knowledge: what debugging strategies work, how to recover from errors, which tool sequences are effective for which tasks. (Some transcripts will also be useful, if the user took no real “steering action” and/or was unable to evaluate if the outcome succeeded or not)

Using coding agents also naturally causes you to create metadata you might not otherwise — you get timestamps, etc. In fact, something I’m really excited about is that transcripts contain the kind of data that might otherwise require “workplace surveillance” to acquire. Someone who does a lot of their work through coding agents ends up, intentionally or not, creating a partial “time sheet” and a “process log”. I personally have found coding with agents to be substantially more pleasant than I imagine working while live-streaming to be. Similarly, if you had asked me three months ago to sit down and write down structured data describing everything I did in a technical project, I would’ve moaned and groaned. When using agents for many of your work tasks, you end up doing this inherently.

In short, it seems nice that coding agents give me a very rich log of decisions I made and what I was thinking without requiring me to record myself or set a timer to write notes every 5 minutes.

Because coding transcripts are so rich (and in some cases, simply quite large files!), fully redacting and filtering them is really challenging. This is a big deal because if you let agents run wild over your files, there’s a pretty decent chance they do “read” the contents of a file at some point and those contents are now in the transcript.

Similarly, if we need to do more traditional annotation, annotating full transcripts is also very laborious! That said, often times we can perform automated assessment — did tool calls succeed, do the tests pass at the end of the day, etc., so I’m not sure thumbs up / thumbs down feedback will be nearly that important here (I still do think that “evaluation data labor” will be absolutely critical for advancing coding agents).

With all this in mind, as I started to play with the latest version of Claude Code, I got very excited about the potential for using coding agents to build tools that will help enable data contribution, data analysis, etc. for this new kind of data.

I first built a slew of very quickly “vibe coded” attempts, but ultimately iterated and merged projects together into two tools that are now relatively substantial: one focused on content management (essentially a bunch of unifying scaffolding around a variety of different static site projects, structured markdown notes, and attempts to cross-reference artifacts more effectively) and one focused on making it easier to use coding agent tools while also making it easier to get really hands-on with the data that they produce.

Extenote [docs|repo|examples] is a schema-driven content management system that keeps structured content and notes in plain Markdown with validated frontmatter and supports reviewing (e.g. just manually look at a random sample of your notes, or run a script to check bibliographic data against reference databases like DBLP or Semantic Scholar) and linking (e.g. cite a paper in a blog post, produce a website with content drawn from a community-curated catalog) pieces of content and then exporting (e.g., to build static sites or to sync with tools built on the AT Protocol) that content. Part of the motivation connects to similar themes: if we’re going to work alongside AI systems that ingest our content, keeping that content in explicit, portable, human and machine readable formats seems increasingly important.

Extenote is heavily tailored towards my personal preferences / my dream “manage all my markdown data in a way that maps to my preferred mental models” tool, but certainly can be useful for inspiration and might actually be something that other people might want to run and fork. I’ll record a video of my main use cases once the semester is fully underway!

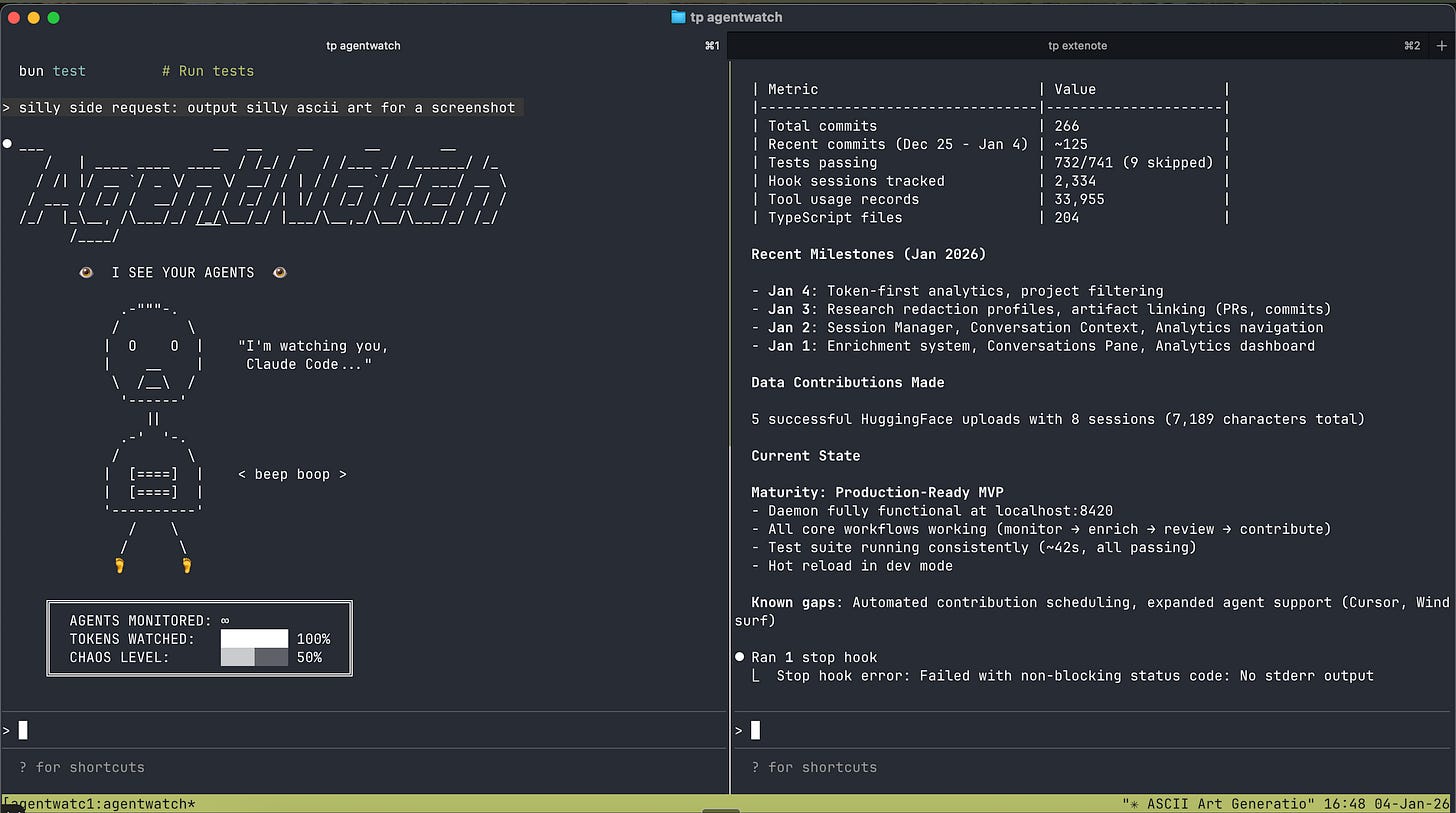

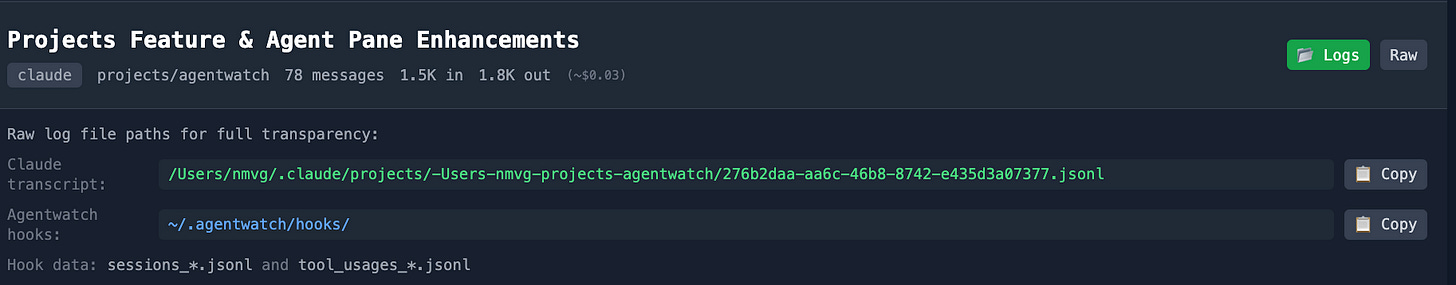

Agentwatch monitors running coding agents, collects additional data to link with agent transcripts, provides built-in tools for analyzing, annotating, and engaging with transcript data (which can be very useful even if you don’t care about data contribution or leverage), and provides a pipeline for users to sanitize and optionally contribute session data. The goal is to very concretely show what flywheel infrastructure might look like for agent traces: inspect what’s being generated, redact sensitive content, annotate with feedback, and decide whether to share.

Agentwatch is a bit more unpolished than Extenote, but it’s also something I’ve been actively using. There’s also some maybe over-personalized features in here, but I think people will find this useful. I expect a lot of other tools like this will pop up in the next few weeks as well, but there’s value in having a tool that’s pretty customized to your exact uses!

(One key tool-agnostic protocol here is the already existing Hooks API. There is a potential to create a protocol that combines redaction, filtering, data sharing preferences, etc. cleanly)

One confession: to show skin in the game, I really want to actually share all the coding agents logs from extenote and agentwatch. Because it’s pretty hard to be 100% sure there’s no secrets in hundreds of transcripts, I haven’t done it yet, but I’m still planning to (this is my milestone for when “bulk sharing” is ready!). As such, I did re-orient the agentwatch sharing workflow around sharing just 1 or 2 transcripts (and I do have an example HuggingFace repository, with mostly uninteresting test data, public here).

Also, important caveat: the sharing component here is not tied to any kind of official research project yet. I’m not trying to solicit contributions from anyone yet, there’s no official “donation endpoint” set up yet. Please reach out if you’re interested, though! If you do want to use agentwatch, you have to bring your own API keys and any sharing to HuggingFace or elsewhere is at your own risk!

For now, the focus is really working through every possible aspect of what sharing agent transcripts would like look like.

Two use cases that are very interesting to me are doing donation drives around supporting public AI systems and/or AI safety research, and forming data collectives around annotated/enriched transcript data to sell back to AI companies.

AI benchmarking research stands to benefit a lot from tools that enable coding transcript sharing. And the “public AI” vision—in which public institutions could train models on transparently-sourced data and share valuation experiments publicly—would benefit enormously from better tooling for users to contribute and annotate their AI interactions.

Feedback very welcome on all of this!

I was a heavy terminal user in grad school, fell off a bit with regards to my knowledge of tmux shortcuts, complex bash commands, and the like, but have been pretty quickly picking it back up with live help from the coding agents and adjusting all sorts of config files in new and exciting ways.

Claude Code can probably help you install Docker for the first time or ssh into a $5/month Ubuntu machine, even if you’ve never touched Linux before!

Fascinating angle on agent transcrpts as a new data modality. The insight that transcripts encode process knowledge rather than just static output is huge for training future models. I've been using Claude Code heavily and the "accidental timesheet" aspect totally resonates - getting structured metadata about decision making without the overhead of workplace surveilance is pretty wild. The security tradeoff between usability and sandboxing is gonna be interesting to watch unfold.