Building a Data Pipeworks for Democratic AI: From Human Knowledge to Records to AI Systems

Focusing on feedback loops -- connecting modern AI to early cybernetics-style thinking -- could help solve looming challenges and support democratic inputs to AI.

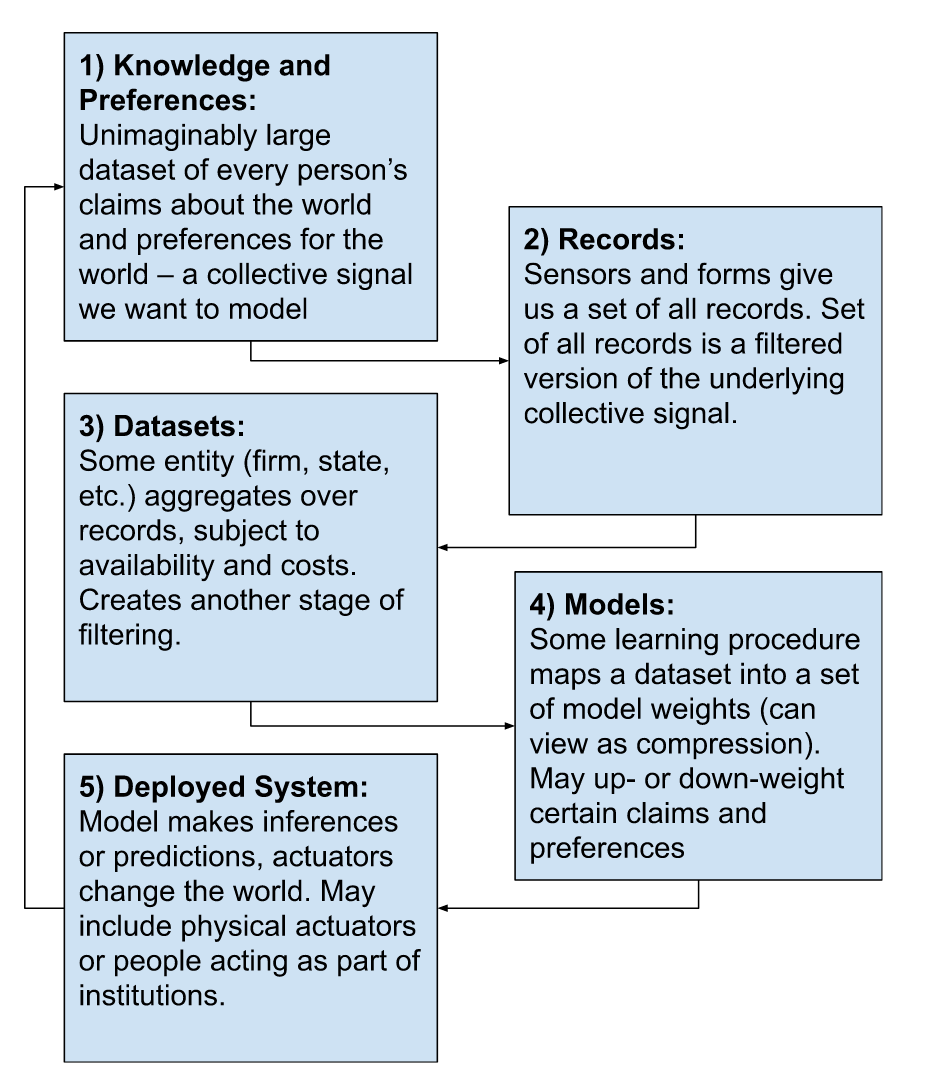

Fig 1. Left: Charon, an early steersman (Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons). Right: A summary diagram showing the five stage Data Pipeworks model.

A preface

This post is going to be a bit different from some of my previous posts. Rather than commenting on data leverage-related news or recent research (which I intend to keep doing – there’s been a lot of exciting movement in the space of data leverage tools, and datalevers.org needs an update), I'm going to share some in-progress writing. Specifically, I’ll share an early draft of a post describing the “Data Pipeworks” underlying modern AI, and how the pipeworks model can support efforts to promote democratic inputs to AI.

This is something of an introductory “chapter”, part of a series of posts that will introduce this pipeworks model and a variety of research questions that I believe the pipeworks can help answer. The posts will also argue for bringing together many disciplinary lenses to tackle looming challenges in AI (especially thorny governance challenges and the looming threat of major social dilemmas related to data), adding to a chorus of calls along these lines.

Key points in this post:

We should consider all the stages involved in creating data for AI: Our knowledge and values (Stage 1) are translated into records (Stage 2), aggregated into datasets (Stage 3), and used to fit models (Stage 4). These models are deployed in systems (Stage 5) that impact the world.

A “Data Pipeworks” model is especially compatible with systems / control/ cybernetics thinking, which emphasizes sources of feedback. One potential source of feedback in the Data Pipeworks is the manipulation of data flow by contributors (“data leverage”). We should work to more precisely specify such cybernetic systems and their feedback sources, as these determine the data with which AI developers work.

It follows that AI is highly dependent on social dynamics and human factors that shape the “landscape of records”. As we rely more on large-scale data-dependent systems like generative AI, a human factors perspective will become more important.

Tracing the flow of data to specific individuals and groups can allow us to quantify the relative weight of an individual or group, and foster pluralistic governance of AI and another notion of alignment.

As data contributors gain agency to affect data flow, building AI systems will require resolving social dilemmas.

At the same time, new levels of data agency and a human-centered perspective may unlock new ways to think about data scaling (e.g. in terms of “units of knowledge”) and new ways to accelerate progress in computing.

At the highest level, this series of posts is really an extended argument for using a broader lens when discussing AI governance. In part, this argument stems from my long term interest in data labor and leverage as a governance mechanism (these concepts emerge when we zoom out from a machine learning problem definition to consider contexts in which data is created).

Fig 2. A visual depiction of zooming out from a specific ML problem to consider the context that determines what data records are created.

However, this broader lens has useful applications beyond specifically advancing the data leverage research agenda – it can be generally helpful to think about upstream factors that shape AI development, as well as taking a feedback-focused approach to thinking about downstream impacts.

In terms of specific problems that motivated this post, I especially wanted to write down a longer argument for why I think we’re inching towards a future in which basically all “AI” work will have a dominant human factors component (some might argue, “always has been!”, and that HCI will “reap the AI harvest”).

I believe we’re going to see a coming wave of data-related social dilemmas (arguably, it’s already started in the realm of art), and pipeworks-thinking can help to solve them in a way that effectively balances technological progress with inevitable ethical challenges that arise. I often find myself a bit defensive about this claim — while the pipeworks will highlight ways that data creators might exert leverage by lowering AI capabilities in the short term, I see this leverage as a part of a “pro-computing” research agenda.

I began my exploration of this concept by thinking about the kinds of questions often posed and solved in human-computer interaction and machine learning venues (the venues that I engage with most), and then asking, how might we start to bring in more control engineering, information theory, communication, economics, and sociology?

After many iterations of writing, I stumbled on a recurring theme: that AI is downstream of human factors, including complex systems with feedback, with the feedback mixing an ecological, economic, and otherwise social nature. I realized that perhaps what I’ve really been grappling with is an attempt to describe the data labor and data leverage concepts in the language of cybernetics (i.e. Wiener's cybernetics). This gave me a reason to be concerned I might be retreading old ground – after all, AI as a discipline arguably came to exist by splintering off from the field of cybernetics! I thought to myself — “Did I just write a lengthy argument that basically just says that the AI field needs to care more about work from… the AI field?” (The circularity of this is fitting, given cybernetic thinking’s emphasis on causal loops).

Indeed, Wiener’s writing from the 1950s and 1960s resonate with ongoing discussions about generative AI’s economic impacts. And certainly work on control theory has continued to advance (and work explicitly taking a cybernetics lens continues as well, see e.g. Zargham and Shorish 2023).

Even if the Data Pipeworks really is just an argument for “Cybernetic AI” (which some might say is just “AI AI”), I think there are some novel ideas here that will be constructive, and I think the old ideas are worth dredging up again.

None of the posts in this series are (yet) structured in a way to answer a specific research question, though they relate to many of my ongoing research projects. If you happen to be reading this and are excited by a particular question or aspect, please let me know!

The following “chapters” of this series are all partially complete, but still being refined. If you’d like to see a full draft of this document, please send me a note!

Thus ends my preface. Onwards to describing the Data Pipeworks.

An Extended Abstract and More Context

This series of posts will present a five-stage model – the “Data Pipeworks" – that aims to describe the process by which human knowledge and values flow to deployed data-dependent systems (i.e., “AI”). Our knowledge and values (Stage 1) are translated into records (Stage 2), aggregated into datasets (Stage 3), and used to fit models (Stage 4). These models are deployed in systems (Stage 5) that impact the world. We hypothesize that considering the full scope of the Data Pipework will be helpful in designing solutions that make AI more prosocial, in particular by enabling realistic assessment of where democratic inputs (including data bargaining) can be implemented. By describing the pipeworks, we also hope to highlight the value of a broad lens that considers human-computer interaction and AI as part of a shared problem-solving framework. A full accounting of the pipeworks will involve negotiating formalisms and problem definitions from across machine learning, human-computer interaction, signal processing, control theory, economics, and sociology, and more. Put another way – because “AI” is dependent on data from a large population, returning to a cybernetic frame that emphasizes steering, feedback, and communication can naturally create democratic AI.

I am hopeful that the zoomed out view of the Data Pipeworks can help to reveal (and solve) several related challenges, including: social dilemmas that arise when people make individual decisions about data flow, support for data coalitions, the design of data markets, characterizing models and datasets (including “synthetic” datasets) in terms of the set of contributors, and more.

Context for the current draft

This current draft is meant to provide one perspective on how many lenses might be brought (back) together to describe and answer questions about the zoomed out Data Pipeworks. My core expertise is in interdisciplinary work in human-computer interaction, machine learning, and responsible AI. I especially welcome feedback on claims about a particular formalism or disciplinary perspective you feel are missing or could be better represented.

Another important note is that this current document has two goals. On the descriptive side, I hope to provide a very thorough description of what we’re doing when we feed human-generated data in generative AI, recommender systems, search engines, classifiers, etc. In a certain sense, simply describing the data pipeworks can be a useful conceptual contribution that might help guide empirical work related to data-centric AI (for instance, answering research questions about how data-related social movements, new data markets, and new data-related regulations might impact AI capabilities).

I argue here that the social dynamics that determine what data records are created and how data flows from people to AI systems are dominant in determining AI capabilities. This means that the design of interfaces that facilitate record creation, sensors that passively create records, and incentives for record creation should all be a top R&D priority for the AI field. I will also discuss the role of social dilemmas and how they could be resolved by carefully designed incentive systems at each stage of the AI pipeline. This comprehensive view can advance discussions about how to produce a more democratic, fair, and robust ecosystem.

However, this document is also influenced by a specific set of views about what kind of governance paradigm for AI we should work towards. Specifically, I am particularly interested in realistic paths towards large-scale democratic participation in steering AI development. It is certainly possible some readers may agree with descriptive claims laid out here but disagree with what I see as takeaways for building prosocial AI.

With that in mind, please send me any thoughts you may have!

The first draft of this was written by Nick Vincent, but I shall shift to using the term “we” from here onwards with the assumption that this will inevitably become a collaborative piece of writing. All errors and missing references can be attributed to the first author.

The Stages of the Data Pipeworks

Stage 1: Knowledge and Values. First, we posit that human activity in the physical and digital worlds generates a "Reality Signal," consisting of facts and preferences, which acts as the raw material for AI systems. We do not intend to make any claims about the actual computability or measurability of reality – rather, we mean to highlight that there exists a theoretical massive set of signals that most “AI” models of human-generated data are sampling from.

Stage 2: Creating Records. Second, we discuss the "Sampling Step," where sensor networks and forms (user interfaces) collect these signals and transform them into structured data records.

Stage 3: Datasets. Third, we describe the "Filtering Stage," wherein records are aggregated into datasets by various organizations subject to social, economic, and legal constraints.

Stage 4: Models. Fourth, we describe the machine learning modeling process as a form of "compression," turning aggregated datasets into useful input-output mappings. We emphasize that the choices made here are highly influenced by the preceding stages.

Stage 5: Deployed Systems. Fifth, we explore how these models lead to actuation in real-world scenarios, capturing economic value and affecting human behavior and the physical world.

Introducing the Data Pipeworks

Overview

In this series, we will lay out a five stage model of the "Data Pipeworks". This model is meant to describe (with considerable use of approximation) how human knowledge and values (stage 1) emerge from the physical world, lead to the creation of records (stage 2) that are aggregated into datasets (stage 3), which are compressed into input-output mapping models (stage 4) embedded into deployed systems (stage 5) that can be connected to actuators that do things in the world. Typically, deployed systems aim to create value for whoever built the system, but also create externalities, and will also create feedback loops by changing the world itself.

There are many ongoing discussions about how we might build a world in which the benefits of deployed AI systems are shared more broadly, perhaps by decentralizing power over monolithic AI systems (e.g., we cast regular votes as part of a giant civic body that governs ChatGPT) or by pushing for a world with many competing AI models (e.g., we all select from a vibrant “pool” of models in a commons). These discussions incorporate aspects of AI governance, AI safety, the economics of automation and prediction, alongside general questions about aspirational arrangements of our political economy

Typically, “technical” AI research contributions operate within a well-defined problem space. For instance, when describing a new modeling technique, authors will provide formal descriptions of the data being modeled and define a clear objective. While academic researchers can rightfully complain that ML and AI work often does not feel as scientific as some other “hard sciences” (see e.g. discussions of “troubling trends” in ML), individual ML/AI problems are typically characterized quite formally (see e.g. here for an overview of many well-defined problems in probabilistic machine learning).

However, questions about sharing the benefits of, and control over, AI exist outside the scope of a single nicely defined optimization problem or other task. They could be implemented as some kind of political and/or economic agent-based model in which tokens representing power and resources are allocated over agents. But this requires contending with how AI systems impact the world and how the records being fed into modeling pipelines came to be. Agent-based models are often something we fall back on when a clean optimization problem cannot be written down.

Indeed, many AI ethics concerns can be framed in terms of some actor failing to consider either downstream model actuation or upstream data collection factors. That is to say, we could draw out a causal graph describing how an AI system impacts the world and take a complex systems approach to modeling our described closed system, but this is not typically what we do in most ML scholarship (with reasonable justification: trying to make predictions about complex systems is extremely challenging). And without a doubt, the current approach of zooming in on specific ML tasks has led to creation of many genuinely useful ML models (though in some cases, we may fall for the Fallacy of AI Functionality).

Building off many conversations along these lines, a key hypothesis motivating this document is that describing the Data Pipeworks in an end-to-end fashion can strengthen efforts to build alternate AI paradigms. In other words, this is a continued effort of “design space mapping”: describing how things are so we can identify levers, knobs, and fertile space where we might insert, or “grow”, a new lever.

Taking a control / cybernetics-inspired approach is especially fruitful because these approaches are hyper-focused on identifying all the levers and knobs that could be a source of feedback for a system.

The goal is not necessarily to try to build some kind of complete agent-based model of the world (again, a daunting task), but rather to capture how human activities “flow” to deployed AI systems with enough fidelity so that when considering a particular intervention, we can speak more specifically about:

what processes are upstream or downstream relative to that intervention

what power structures control what happens upstream of that intervention – this can help us be realistic about what interventions might achieve.

where feedback loops are likely to be of concern.

Eventually, writing out the specification for a formal cybernetics-style system (perhaps drawing directly on ecological or biological models) could be feasible. And this system could be explored by a carefully designed (wrong but useful) agent-based model.

In describing the full flow, we can do a better job reasoning about how distinct interventions – e.g. tools that empower data creators to engage in collective action, new laws that affect AI systems are deployed, new licensing norms that determine how model weights are shared, new ML work that explains model capabilities in terms of data – fit together and complement, or depend on, each other.

Specifically, we’ll describe our pipeworks in terms of a signal generated by the collective activity of all humanity that is passed through three filters – the creation of records, the aggregation of datasets, and algorithmic model training – and connected to some set of actuators. Each actor who ultimately builds/deploys an AI system is subject to their own unique set of these three filters (based on the records they have access to, how they aggregate data, and choices they make in implementing their learning algorithm).

In describing the Data Pipeworks, we’ll naturally have to start defining different classes of agents, which will become useful when we do want to use computational modeling to explore certain parts of the pipeline (accompanied by the knowledge these models will be wrong in some ways but useful).

Fig 3: A diagram describing all five stages of the Data Pipeworks.

Key Claims

The Primacy of Social Dynamics and Human Factors

In describing the AI Pipeworks, we are making an argument that social dynamics and human factors are dominant factors in determining AI capabilities (because things that are more upstream in the pipeworks dominate). This is not too wildly controversial – after all, if AI aims to model human behavior or the production of human outputs, then of course any “AI'' related activity is circularly dependent on how humans behave. The Data Pipeworks framing can help us describe how the specific complex systems and emergent behaviors that underlie record creation (and perhaps even dataset aggregation and model training) shape the landscape upon which we can do technical work. To the extent that “technical” AI work aims to be a sort of civil engineering (building sound structures within our “space” of knowledge), social processes determine our topology, which may at times block off entire realms of exploration. In geographies with no rivers, there’s no need to build bridges. In geographies where the soil is too loose, we cannot guarantee certain measures of stability, etc.

We can think of record creation, dataset aggregation, and model training as three filtering stages that heavily influence the data distributions that many computer scientists and mathematicians doing technical ML work explore and work with mathematically. This in turn can drastically change training and evaluation of AI models.

Interfaces, Sensors, and Incentives are “Core AI”

Further, the AI Pipeworks makes the case that the design of interfaces and sensors -- and the incentives mechanisms that guide interactions with interfaces and sensors -- should be a top tier R&D priority for the AI community. HCI and technical ML research goals are deeply intertwined. Any widely adopted interface designs will have major downstream effects on choices relating to dataset management, model training, and model deployment. Again: if a core group of “technical” ML and AI primarily want to do math and engineering, the social factors shape the landscape on which that technical work will be built.

Describing data flow in stages can help us design interventions that can improve AI capabilities or give groups of people more power. Ideally, we can do both at once by reducing inequalities in power to healthy levels while improving capabilities of AI systems that are broadly available.

Social Dilemmas in AI

We’ll also make a conjecture about social dilemmas and AI that I believe the Data Pipeworks model can help resolve:

The record aggregation tasks at the heart of many AI technologies enable social dilemmas. AI systems are (almost always) shared, quasi-public goods. Their creation can be well-described as a classic collective action problem: a group of individuals have (heterogenous) access to "building block resources" they can throw into a shared pot to build some good with shared benefits, and varying levels of interest in the good. In other words, the process of going around house to house to collect records to train an AI system looks a lot like going around house to house to collect donations to renovate the park in the town square.

In some dataset-building contexts, there is great potential to free ride (some people skate by without contributing data because a system is already good enough). In others, there is potential to fail to achieve critical mass (people choose not to contribute data, even if large-scale data contribution would lead to a broadly beneficial system). In practice now, these social dilemmas are often solved by a "dictator solution": tech companies leverage information asymmetry to just collect records describing the activities of people who may not realize they're playing a shared goods resource sharing game.

In a world with increased data-agency-per-person, a dictator solution doesn’t work. To get models with similar predictive quality, we need carefully designed incentive systems at each stage of the AI pipeline.

One solution might simply involve placing more types of record creation in the domain of formal markets (i.e., more crowdwork marketplaces or more data escrow-type systems like DataStation).

Better yet, we might solve the social dilemmas by supporting markets in which the primary actors are data coalitions acting on behalf of individuals.

Connecting with formalisms from machine learning, information theory, signal processing, and more

In the section below describing the five stage model, we mostly avoid formalism. However, a key value add of this framework is the ability to translate between different lenses. In the Appendix, we will begin to describe the Pipeworks using three different disciplinary perspectives and their norms around formalism: machine learning, information theory, and signal processing.

The end of the Introduction

This ends my introductory post to the Data Pipeworks. Please do let me know if you found this helpful. Or alternatively, let me know if you found this too indulgent or meandering, and just want to see more discussions of recent news and recent papers. If you made it this here, I certainly want to hear what you think!

I hope to share the following “chapters” (expanding on the individual stages of the pipeworks, and then summarizing specific research questions and computational modeling approaches that emerge from this thinking) on a semi-regular cadence.

Thanks Nick, always appreciate your insight. At the Digital Trade and Data Governance Hub, we are also thinking a lot about democratic participation for steering AI development (we just held a conference on data governance and generative AI https://datagovhub.elliott.gwu.edu/calendar_event/data-governance-in-the-age-of-generative-ai/)

Looking forward to the next post on this!